« 6.6: Tint and Transparency |

7.2: Mouse Interaction »

It’s time to look at interactivity in Processing. You can program Processing to work with a range of input devices, such as microphones, cameras, gamepads, or even something you’ve built with an Arduino board. For this lesson, though, we’ll stick to plain-old keyboard and mouse input. You’ll look and building basic interfaces for painting freely and drawing faces. In the process, you’ll discover that Processing’s standard functions are not exactly purpose-designed for constructing user interfaces. However, the lesson also includes an introduction to the ControlP5 graphical user interface library. ContolP5 provides a suite of essential control widgets, such as buttons, checkboxes, sliders, toggles, and text-fields, thereby saving you the time and effort of having to create them from scratch.

We’ll also touch on a few game development concepts, specifically collision detection and delta time.

Some User Interface History

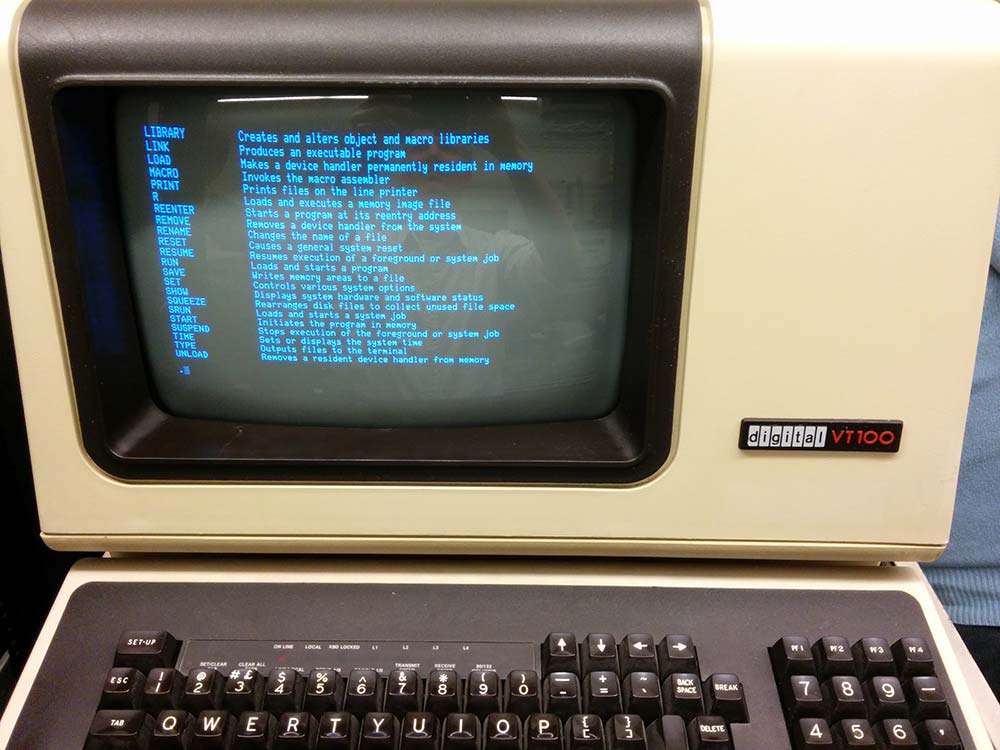

It may hard to believe, but there was a time when computers had no video displays. We’ll skip over that early chapter of computing history, though, and begin at the Command Line Interface (CLI). The first computer monitors couldn’t display much more than text and basic graphics, but this was enough to support a handy CLI. By typing a series of commands, one could instruct a computer to perform its various functions.

Autopilot [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

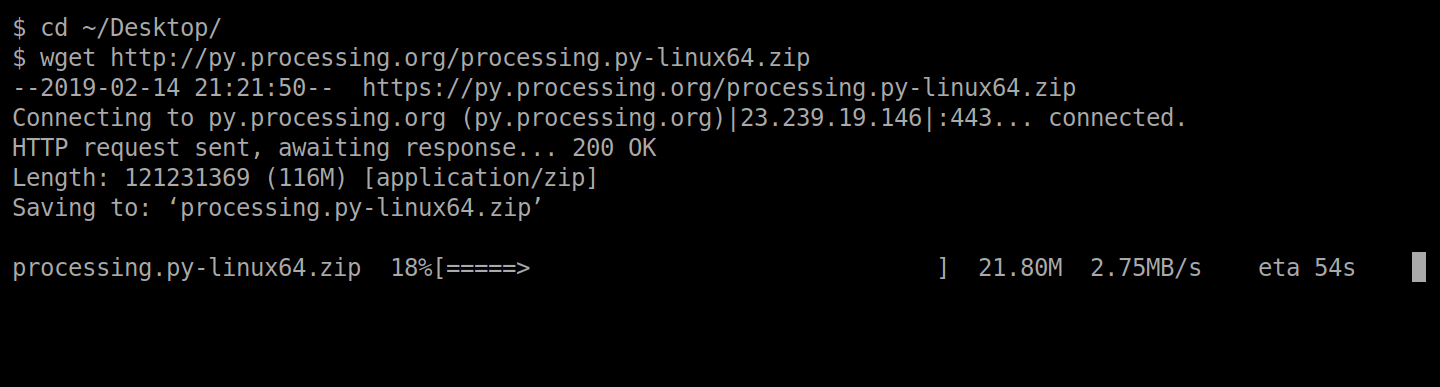

You may be surprised to hear that the CLI is far from dead and buried. While it may no longer be the predominant means of interfacing with computing devices, system administrators and programmers still rely on it for many daily computing tasks. Furthermore, you are likely to be surprised by how much can be accomplished just typing instructions. As anybody who has mastered the command line can testify, it’s more efficient in various situations, particularly where repetitive tasks and batch processing are involved.

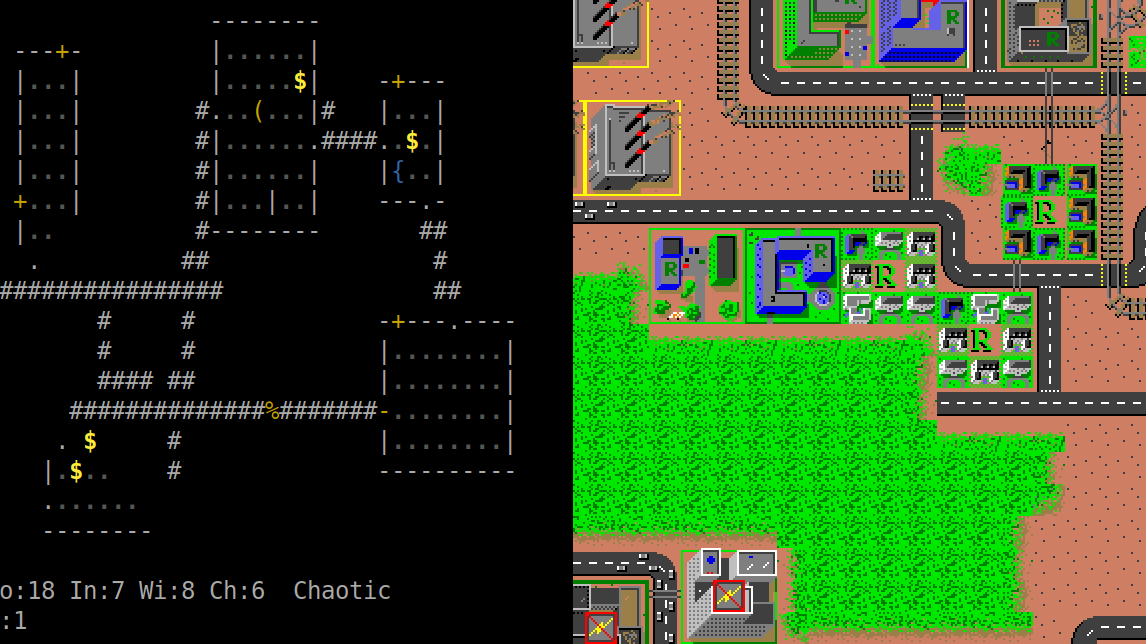

In the above example, you can spot two $ symbols; each is referred to as a prompt, although the symbol displayed can vary between operating systems. The prompt signifies that the computer is ready to accept input. Two commands have been used here: cd for changing directory; and wget for downloading a file from a web server. In this case, I’m downloading the command-line version of Processing.py to my Desktop. That’s right – you can run Processing sketches from the command line without opening the editor.

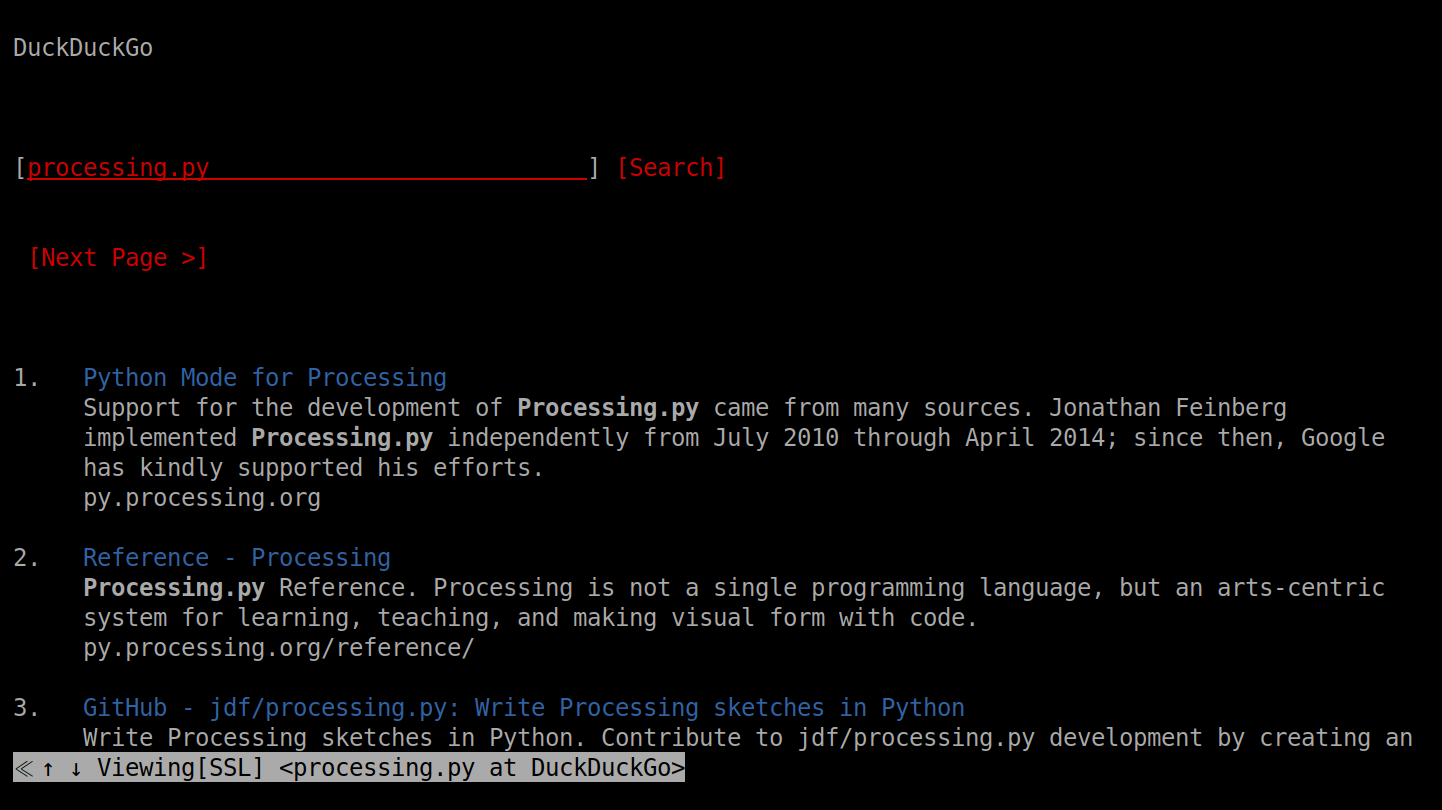

A Text-based User Interface (TUI) is a kind of blend between the CLI and modern graphical interface. For example, take w3m – a text-mode web browser. Using the arrow keys one can navigate websites, albeit in with limited styling and no images.

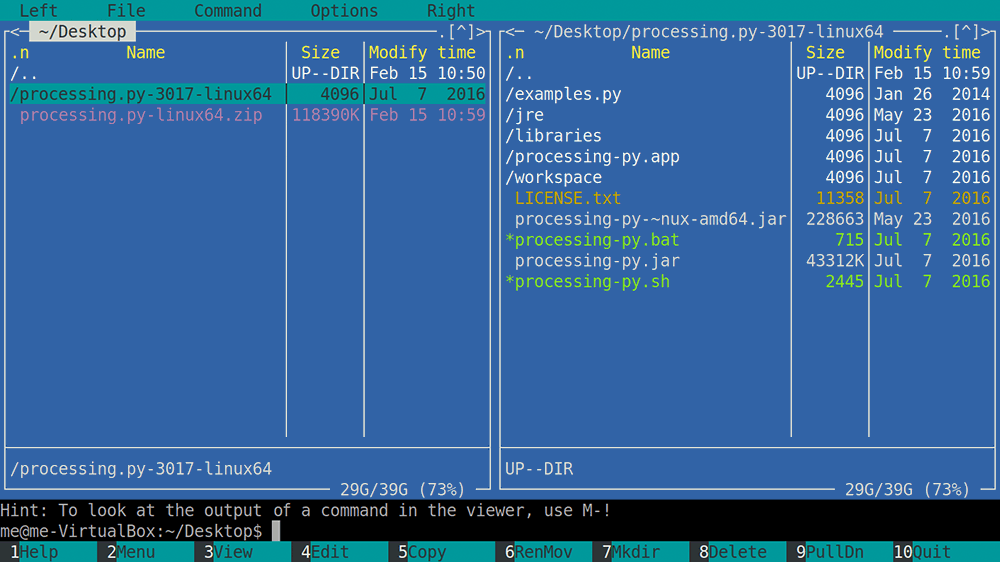

For richer text-based interfaces, many old systems included semigraphics. You can think of semigraphics as extra characters that allow you to ‘draw’ with type. Modern systems have adopted many of these characters; for instance, you can copy-paste these symbols straight from your web browser into any text document: ♠ ♥ ♦ ♣. Additionally, Unicode (basically, a collection of all of the characters a computer can display) includes over a hundred box-drawing characters for constructing TUI interfaces.

┘ ┐┌└ ┼ ─ ├ ┤ ┴ ┬ │

In text-mode, computer displays are measured in characters as opposed to pixels. For instance, the ZX Spectrum, released in 1982, managed 32 columns by 24 rows of characters on a screen with a resolution of 256×192 pixels. Because text-mode environments rely on mono-spaced characters, box-drawing characters will always align perfectly.

It’s important to mention, though, that many CLI- and TUI-based systems were not incapable of rendering raster graphics. There were text and graphics modes that a system could switch between. Take games for instance. Of course, text-mode games – like the dungeon crawler, NetHack – operate in text mode, but for games with graphics, the computer would switch to addressing individual pixels. Even today, PCs still boot in text mode, before shifting to graphics mode to load the desktop environment.

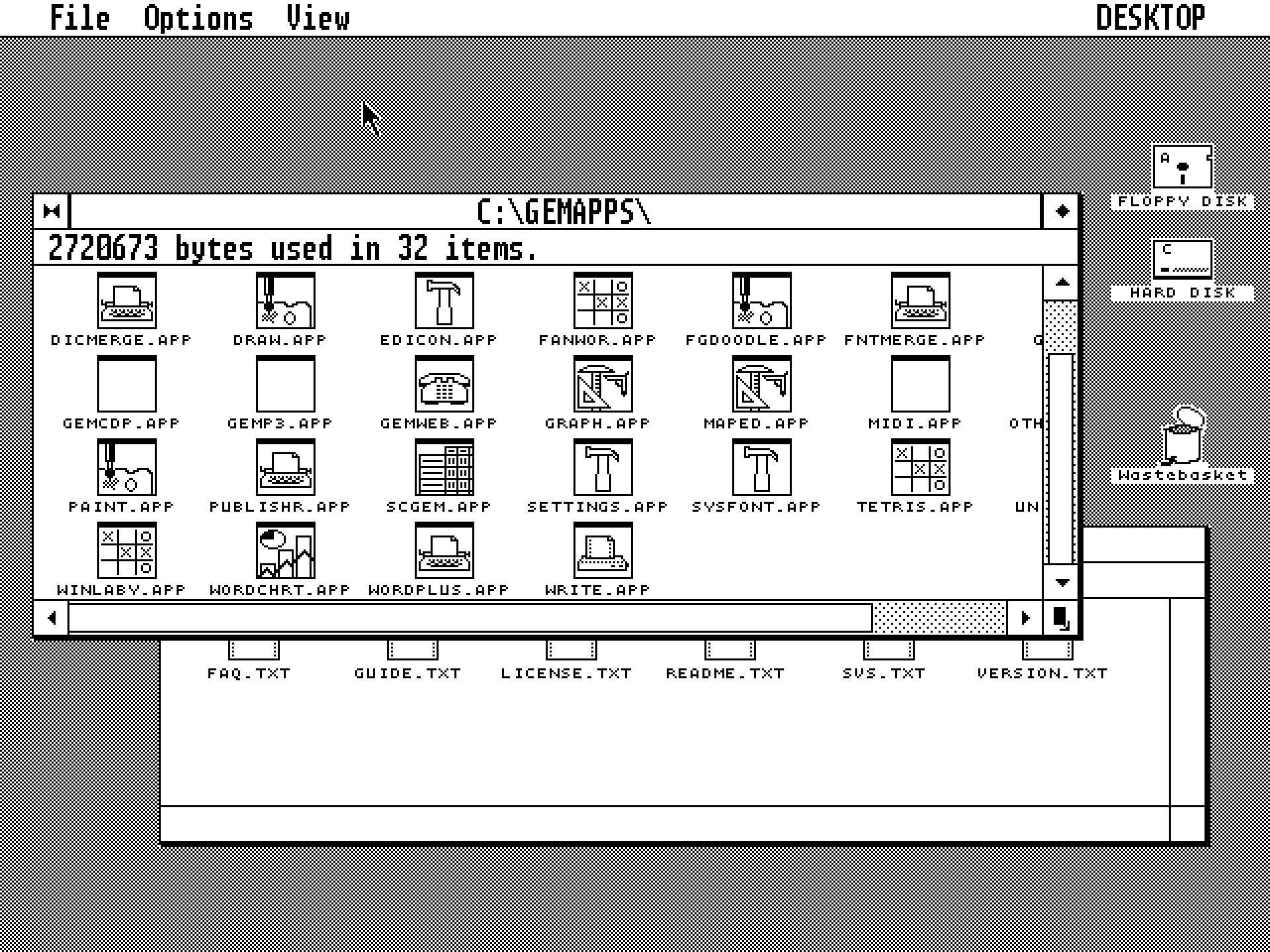

A Graphical User Interface (GUI) allows for interaction through the manipulation of graphical elements. You routinely make use of such interfaces to interact with your file manager, web-pages, application software, and mobile phone. To narrow down GUIs a bit, I’d like to focus on WIMP interfaces. The Windows/Icons/Menus/Pointer paradigm was developed by Xerox PARC in 1973 and popularised by Apple’s Macintosh in 1984. This has been massively influential on graphical user interface design, and the WIMP-meets-desktop environment has remained fundamentally unchanged since it’s inception. The desktop metaphor was particularly intuitive as it mimicked the very items that computers sought to replace – documents, folders, notepads, and the forgiving trashcan for retrieving deleted files. With a GUI, gestures and menus replace CLI commands. For example, rather than typing “mv” commands, a user can drag-and-drop files to move them between folders (directories).

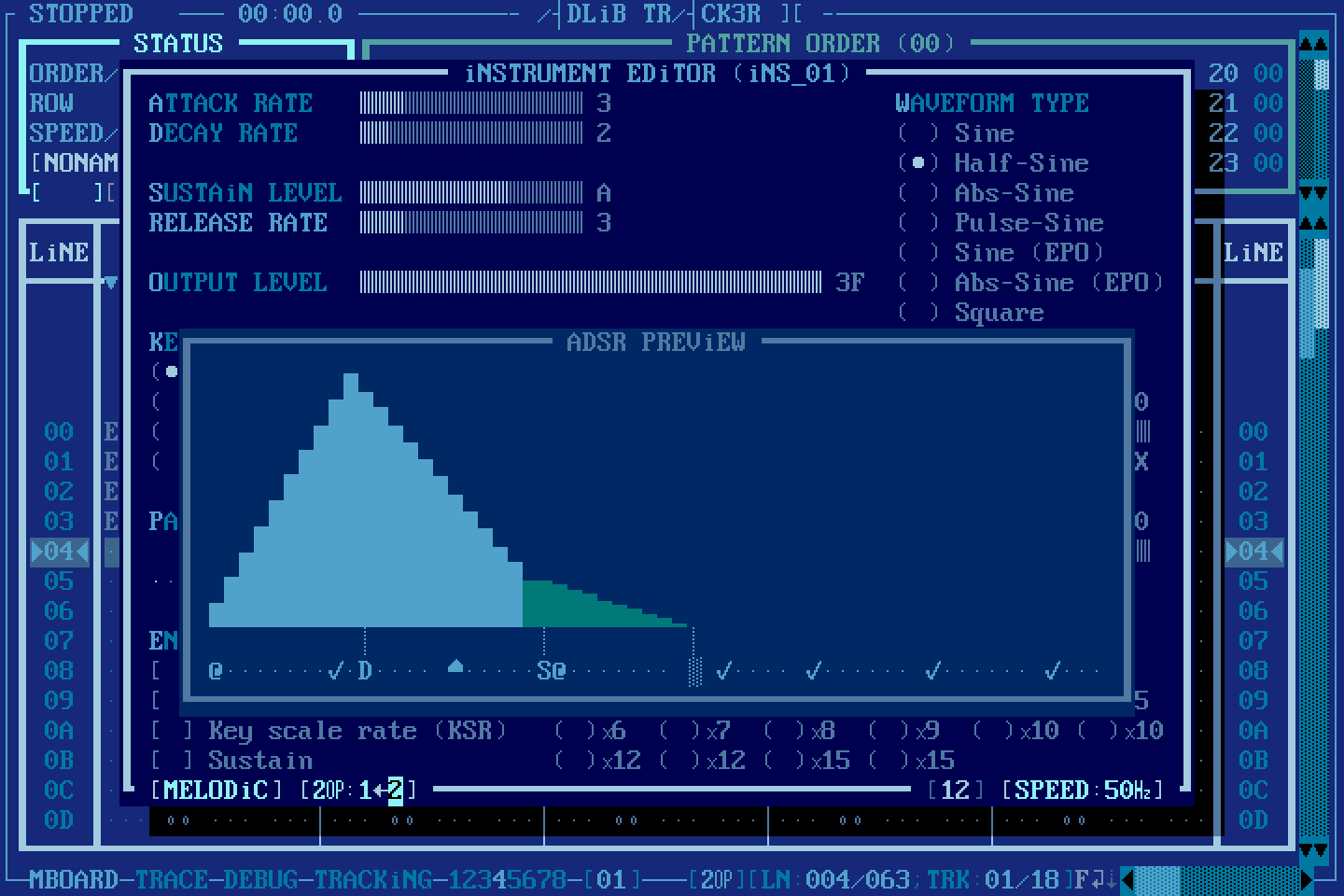

Apple licensed certain GUI features to Microsoft for use in Windows 1.0 but sued them when features like overlapping windows appeared in Windows 2.0. The district court ruled in favour of Microsoft. Regardless of the legal outcome, Windows 1.x and 2.x were slow, clumsy, and poorly received. Most Microsoft users elected to stick with the Microsoft text-mode environment, MS-DOS. With VGA-colour, fonts, mouse support, and lightning-fast performance thanks to text-mode, MS-DOS TUIs grew to become remarkably advanced.

Many significant hard- and software developments paved the way for WIMP environments. Arguably, though, it was the invention of the mouse set that the process in motion. It was Douglas Engelbart – in collaboration with computer engineer, Bill English – who created the first mouse prototype in 1964.

SRI International [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

In reality, the development of GUIs involved many people over many years. As the field developed, it spawned new disciplines. Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) researchers emerged in the early 1980s. Bill Moggridge and Bill Verplank coined Interaction Design (IxD) in the mid-1980s to describe the practice of designing interactive digital products – Moggridge felt this was an improvement over his earlier term, Soft-Face. Since then, User Experience (UX) designers, User Interface (UI) designers, and Information Architects (IA) have all entered the scene. I’d imagine that some labyrinthine, mutant Venn diagram exists somewhere to help explain how all of these disciplines relate to one another.

Of course, advances in interaction design are not limited to software. Touchpads found their niche in laptops (as well as MP3 players and nifty music synthesisers). Touchscreens hit it big with tablets and smartphones. Then there’s gesture recognition, force feedback, GPS, and augmented reality. Voice recognition has gained newfound traction thanks to enhanced natural language processing. In some respects, speech interfaces represent a coming full circle – instead of typing in commands at the CLI, we now issue them with our voice!

Although we’ll stick to keyboard/mouse input in this lesson, you are encouraged to explore other means of interaction in your own time. GUI programming features prominently in many software and web development projects, so there are plenty of GUI toolkits out there. HTML, for example, is purpose-built for constructing web-pages. For Python, there’s PyQT, Tkinter, and Kivy, to name but a few. You’ll discover that programming basic buttons without any readymade widgets is painful enough, not to mention checkboxes, sliders, drop-down lists, text-fields, and windows. I’ll try to provide a few tips on good user interface design in the process, but this field really requires another book(s) to cover in any proper detail.

7.2: Mouse Interaction »

Complete list of Processing.py lessons